Project scheduling is the key to ensuring the original project plan and final project outcome are at least close enough to call the project a success. It’s the map that guides the ship. Good project managers look at the schedule constantly, sometimes on a daily basis, and take the actions necessary to stay on track.

Because the definition of a project requires it to be a temporary endeavor, with a defined beginning and end, the schedule is virtually always a major factor in the success of the project.

Someone is awaiting for the project’s final product, and arriving at the destination on time and budget is of primary importance.

Developing a project schedule involves five steps:

- Defining the Activities

- Sequencing the Activities

- Estimating the Activity Resources

- Estimating the Activity Durations

- Developing the Schedule

Defining the Activities

A project schedule needs to be built on a strong foundation. This foundation occurs in the form of a task list, which sounds simple but it carries the weight of project scheduling and control throughout the project so it should be chosen carefully. This task list is called a work breakdown structure (WBS), although the PMBOK guide differentiates between the WBS as a list of project phases and task activities which are smaller children to the WBS elements. I will refer to the task list as a WBS.

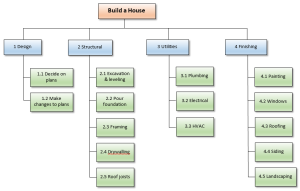

The format of the WBS is irrelevant. A simple list will work, or a graphical representation of the tasks can aid in producing the list. The activities can be organized into “levels.”

The format of the WBS is irrelevant. A simple list will work, or a graphical representation of the tasks can aid in producing the list. The activities can be organized into “levels.”

The tasks should divide the project into work components that make sense and provide a logical sequence to the work. Here are a few other considerations:

- Reliable estimating. If the task is too general it will be difficult to estimate its cost, thereby reducing the reliability of the overall project estimate. On the reverse side, if the task is too specific it will be too onerous to manage.

- Based on deliverables. If a task results in a deliverable, it should contain its own task (or parent task containing multiple child tasks).

- Responsible Party. If a task has a separate responsible party, or is subcontracted to a third party, it should be an independent task.

- Match to cost accounts. If your organization is tracking effort or resources in various cost accounts, the WBS can be structured accordingly.

- Length. There is no correct length to a task activity. But I would suggest that if you have greater than 10 items within one level, it becomes less manageable and another level should be created. It is generally suggested to follow the “8/80 rule,” which states that a task should be between 8 and 80 man-hours. Tasks shorter than a day are difficult to manage, and tasks longer than two weeks are difficult to track accurately.

- It should be measurable. It should be easy to put a progress amount (percent complete) on a task at any time. If it is difficult to measure the progress, the task should be subdivided into smaller parts.

The “100% Rule” states that the WBS should contain 100% of the work within the project, not more and not less.

Because the WBS will be used for many project management functions, like scheduling, cost estimating, and project controls throughout the project, each task should be given an identification number and description which will follow it throughout the project.

Sequencing the Activities

Once the project activities are chosen, the relationships between them must be determined. Although it is true that most tasks will start when the previous task finishes, this is not always the case. The possible dependencies are:

- Finish-to-Start (FS): This is the most common, whereby task B cannot start until task A finishes. For example, you can’t place a fence post until you’ve dug the hole.

- Finish-to-Finish (FF): Task B cannot finish until task A finishes. For example, planting seeds cannot start until the soil is finished placing.

- Start-to-start (SS): Task B cannot start until task A starts. An example would be that the fencepost cannot be installed until the concrete has begun pouring.

- Start-to-finish (SF): Task B cannot finish until task A starts. This one is rare. An example would be when environmental permitting applications cannot finish until soil monitoring starts.

Oftentimes a task will be dependent on some event outside the project, and hence outside the project manager’s control. This is called an external dependency, and an assumption must be made when including the task within the project. All relevant stakeholders should be made aware of the assumption. The opposite, an internal dependency, is much preferred.

Sometimes a task cannot start until a certain time period has elapsed between the tasks. This is called a lag time, for example, “task B has an FS relationship to task A with a lag time of 10 days.” The opposite, when a task must start a certain time period before the dependency, is called a lead time.

Dependencies are not essential, especially for small projects. But they can be quite useful, especially when using software. Dependencies allow you to adjust any one part of the schedule and quickly see how overall completion dates change.

Estimating the Activity Resources

Once the sequencing of the activities is determined, the resources for each activity must be estimated. This takes the form of estimating the number of units required of the following items:

- Labour

- Equipment and tools

- Facilities

- Funding

- Any other item necessary to complete the task

But just because a resource is necessary doesn’t mean it’s available. To determine the availability of resources, the project manager consults a document called a resource calendar. This is a document that states the availability of a resource, for example, “Johnny Worker is working on project X from Sep. 1 to Sep. 30.” Obviously, the new project being planned cannot use this worker at that time unless arrangements are made with the other project manager.

Estimating the Activity Durations

Taking into account the resource requirements for each task, as well as the resource calendars, the project manager proceeds to estimate the duration of the activities. Estimating also utilizes the following techniques:

- Analogous estimating: If the task has been performed before on a different project, the actual duration of the task can be very beneficial information. Even if it was similar, the difference can often be estimated better than the entire task can when not in possession of this information.

- Parametric estimating: This type of estimating breaks down the work into the major variable and uses a standard unit rate. For example, the square footage in a building construction project can be used to arrive at a reasonable rate for the entire project.

- Three-point estimating: When dealing with considerable uncertainty, a three point estimate can aid in achieving confidence. When using this type of estimate, three values are estimated: Optimistic, most likely, and pessimistic. They can then be averaged (triangular distribution), or a beta distribution can be used:

- Estimate = (Optimistic + 4 x Most Likely + Pessimistic) / 6

If you need to use three-point estimating, it might be better to use the pessimistic number rather than spending your energy finding a an applicable averaging formula.

Contingencies are an important part of activity durations. It is common practice to estimate an activity duration and add a certain percentage, often 10%, to cover any potential overruns. This is good practice, but the project manager should beware also of Parkinson’s Law, which states that:

Work expands to fill the time allotted to it.

Developing the Schedule

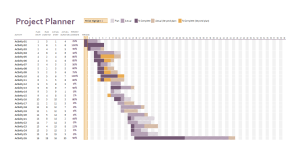

There is no standard format that should be used, in fact, Microsoft Excel is as good a tool as any. Here is an example using Microsoft Excel (this was one of the first templates in my version).

And here is an example using the free ProjectEngineer project management software available at this site:

And here is an example using the free ProjectEngineer project management software available at this site:

The goal is to create a schedule that is achievable. That means it needs to have meaningful start and end dates that are achievable but don’t provide too much room for slacking.

The project schedule should be created at the outset, approved by the project sponsor, and concurrently set in stone. Changes need to go through official change procedures, including approval by the project sponsor. If the project is behind schedule, it cannot be revised. Rather, a new schedule must be produced which applies from this day forward. The old schedule applied previous to that day. Do not complicate the fact that there has been a schedule change.

It can be as simple as renaming the project schedule to “version 2,” specifying the dates the old schedule applied, and getting approval from the project sponsor (if applicable).

Scheduling Software

There are many software alternatives out there which make scheduling easier and allow for complex networks of tasks and dependencies. Traditionally, desktop applications like Microsoft Project and Primavera Project Planner have been purchased and installed on a desktop or network.

Lately there has been an explosion of online, cloud based alternatives which allow you to log in and create schedules online. I have even developed one which for which we allow free access, located at www.projectengineer.net. Schedules can usually be shared with other members of the project team, client, or sponsor. Changes can also be easily communicated. Regardless of which online alternative you choose, it could be a worthwhile investment.

If you’ve never created a schedule before, this can be an empowering exercise. Say goodbye to projects drifting aimlessly out to sea and prepare to step your project management skills up a notch.

More Information

If you’d like to learn more about project scheduling, please try our Project Scheduling Tutorial.