Starting from a point of almost complete ruin after World War II, the Toyota Motor Company rose to become the largest car maker in the world in the mid-2000’s.

This resulted in many inquiries into the source of their success. Starting in 1988, the engineers and architects of Toyota’s success began to open up. As a result, the Toyota Production System (TPS) has evolved into the modern concept of lean manufacturing and is revered today as the gold standard for process improvement and control.

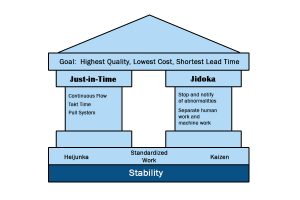

There are two central concepts:

- Just-in-Time Manufacturing

- Jidoka (Automation with a Human Touch)

To implement the system, three wastes must be removed from the production system:

- Design out overburden (muri)

- Reduce inconsistency (mura)

- Eliminate waste (muda)

These concepts were summarized in the Toyota Production System “house”:

Just-in-Time Manufacturing

The Toyota Production System is often used interchangeably with Just-in-Time Manufacturing, probably because it is the most readily visible part of the system to an observer. However, just-in-time was originally considered only one component of the TPS. Indeed, concept of just-in-time manufacturing was identified in Taiichi Ohno’s 1988 publication revealing their production methods together with Jidoka (automation with a human touch) as the two foundational concepts of the system.

Just-in-time manufacturing means that storage of components is minimized. The components arrive at the assembly line at just the right time to minimize storage within production. It also means the output of the whole plant is produced on a made-to-order basis with minimal inventory storage at the downstream end of the production process.

In non-lean factories, the highest priority is minimizing the downtime of people and machines. This produces profitability reports for management that show the plant is fully utilized, but it doesn’t account for efficiency levels. For example, when a 100% utilized machine produces a defective part that must be re-processed, the whole processing effort has been wasted. The machine was fully utilized in production, but it was definitely not fully utilized in revenue generation for the organization, the larger goal. Likewise, when the machine produces a component that gets stored as inventory for months, revenue is foregone. There is a time component to all of the business’ operations – The company’s income and expenses are reported per year or per month, and the people get paid yearly or monthly. Hence, the delay in receiving payment by stocking inventory affects the bottom line.

Some plants even attempt to maximize inventory, thinking that the more components they have readily available for a rush order the less likely the assembly line is to stop because of availability issues. And there is some rationale for this.

But the Toyota Production System is clear, that just-in-time is part of the secret to their success.

Jidoka (Automation with a Human Touch)

The japanese word Jidoka (automation with a human touch) in the Toyota Production System means that the machines attempt to monitor when a process has broken down and stop the assembly line automatically. This allows one person to monitor multiple machines rather than one person for each machine.

The japanese word Jidoka (automation with a human touch) in the Toyota Production System means that the machines attempt to monitor when a process has broken down and stop the assembly line automatically. This allows one person to monitor multiple machines rather than one person for each machine.

This translates into two quality control mechanisms:

- Each production station contains a measurement device for the applicability quality metrics, and if the measurement is negative, the production station is not allowed to release it to the next downstream one.

- Each production station contains a “big red button” which stops the entire assembly line if an operator notices a quality problem. Assembly line workers were not only allowed to use the button, it was their responsibility if they saw quality problems being passed down the line. This came with mandatory training prior to working on the production line.

To accomplish Just-in-time and Jidoka, the three wastes are removed from the production system: Muri, Mura, and Muda.

Design Out Overburden (Muri)

The first of the objectives is to design out muri, which means beyond one’s power, too difficult.

Overburden results when a process is too complicated or difficult for the workers (or machines) to be able to perform reliably.

The solution is to standardize the work. Each process should have a standard written procedure which eliminates variation and makes it clear to everyone what the worker is to do.

For example, in non-Lean factories a worker might be given a task to place and tighten four bolts at their station. When the bolt inventory is low, they must call the supply department to replenish the inventory. In contrast, the Toyota Production System would create a written procedure which tells them which order to place the bolts, how far to tighten them, and how many seconds this action should take. When the bolts are depleted, the procedure specifies who to call, and they are tasked with replenishing the inventory.

Reduce Inconsistency (Mura)

The second of the three objectives in the Toyota Production System is called mura, which means unevenness and irregularity.

It is very harmful to plant productivity when the demand for its products is inconsistent. In fact, most plant managers would rather have low, steady demand for its products than wildly gyrating demand that is sometimes extremely high.

The way to avoid mura is for the plant to operate on a “pull” basis. That is, each process in the system must request the components from the previous step. Hence, the parts do not get produced until they needed and the finished products are absorbed by the market as soon as possible. This is accomplished via kanban cards, which can be physical cards or electronic tracking mechanisms.

Eliminate Waste (Muda)

The third of the three types of waste is also the one which is commonly associated with the Toyota Production System, probably because it is the easiest to implement and most intuitive to apply.

The third of the three types of waste is also the one which is commonly associated with the Toyota Production System, probably because it is the easiest to implement and most intuitive to apply.

The japanese word “muda” means “Futility, Uselessness, Wastefulness.” Hence, this third concept within the Toyota Production System refers to the continuous improvement of the production system via the elimination of wasteful elements within the production cycle.

There are 7 types of waste that have been identified by Toyota engineers which receive the focus of production efficiency:

- Transport

The unnecessary transport of component parts, equipment, and machinery is a waste that should be eliminated. When parts are moved to interim locations, or more parts could be moved at one time, an element of waste occurs because the material did not have to be moved. The waste can be removed by minimizing the transport of materials. This category also includes things like transporting materials between plants and transporting equipment and machinery. - Inventory

The unnecessary storage of inventory is a waste because it requires expenditures for floor space and the production of unsold products. When too much inventory exists, that is, excessive numbers of components stored at the production plant or too much finished product is produced, the storage of that inventory requires space which results in waste. - Motion

The excessive movement of people and equipment to produce the products is a wasteful endeavor that should be eliminated. The total number of motions required to produce the products should be minimized. The number of people movements required to assemble the product must be minimized. - Waiting

Delays incurred in a production step while waiting for a previous production step are wasteful. This is a common occurrence, and it results in a significant cost to the production facility. - Overproduction

Producing too many end products requires that they sit idle until they are sold. In the meantime, the components must be purchased and the unsold products stored. All of these items have associated cost hence they are considered waste to the value stream. - Overprocessing

When the process is poorly designed, excessive processing of the components during assembly is a waste that can be eliminated. - Defects

Once production has completed, the process of repairing or replacing defective products suggests that the quality of production could be improved. The cost of repairing defects comes right off the bottom line. The process of managing defective product requires customer service and maintenance personnel. And in addition, the reputation of the company suffers as a result of defective product. Hence, defective products are a waste to the value stream and should be minimized.

One more waste was added later:

- Unused skill

When a workers has knowledge or skills that would make the production more efficient, but this knowledge or skill is not being used, the process is wasteful. The organization should seek to ensure that all workers are trained and that the training is implemented into the production process.

Conclusion

It is not an exaggeration to say that the Toyota Production System turned manufacturing on its head.

The architects have been open about the secrets to their success, hence much has been written and analyzed about the TPS over the years. However, today it has evolved into the modern concepts of lean manufacturing, which is significantly better documented and supported. Therefore, practical implementations (non-academic studies) should focus on the 5 principles of lean manufacturing.