If I asked you how far behind your project was, could you tell me in quantitative terms?

Most people know the basic status of various tasks:

“Well, that report was a week behind and Johnny should’ve finished his analysis by yesterday.”

But that’s not good enough. Project management standards dictate that the project manager knows how far behind (or ahead) the project is in quantitative terms. If you want to be a good project manager, you need to learn to use Earned Value Management.

How to Calculate Earned Value

If you don’t already track Earned Value, it can be done without software in 10 minutes per week, and in this article I will show you how. At the engineering firm I manage, we do it weekly and I believe it is the single biggest driving factor for our projects.

To get started, Earned Value Management requires that the project be broken down into tasks (a work breakdown structure), and each task requires the following pieces of data:

- Start and end dates

- A task budget.

Most projects already have these defined. If you don’t, you can define them and measure against that. If you only have an overall project budget, you can still itemize each task budget on a percentage basis and track against that. But you need a baseline to track against.

For each task, the following definitions are required:

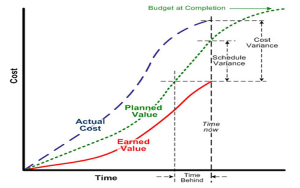

- Budgeted Cost of Work Scheduled (BCWS): At any point in time, the amount of the task that is supposed to have been completed, in dollar terms. A linear interpolation works as good as any. Also known as Planned Value (PV).

- Budgeted Cost of Work Performed (BCWP): At any point in time, the amount of the task that is actually completed, in dollar terms. Also known as Earned Value (EV).

- Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP): The actual cost to the organization of the work that has been performed.

To calculate Earned Value, perform the following tasks:

- Estimate the expected percent complete based on the schedule. For example if the start and end dates of the task are Dec. 1 and Dec. 10, respectively, and it’s Dec. 3 today, the expected percent complete is 30%.

- Convert this to a monetary value by multiplying by the task budget. This is called the Planned Value (PV), also known as the Budgeted Cost of Work Scheduled (BCWS).

- Estimate for the actual percent complete of each task, based on the number of hours of work left to complete it.

- Convert this to a monetary value by multiplying by the task budget. This is called the Earned Value (EV), also known as the Budgeted Cost of Work Performed (BCWP).

- Calculate EV – PV (or BCWP – BCWS), which is called the schedule variance.

- Graph the results.

There is software out there for entering your project schedule and generating an Earned Value graph, but this is the procedure they use. In the absence of software, you can generate an excel spreadsheet and simply update the numbers every week (or whatever time period works for you), like I said, in 10 minutes or less.

There is software out there for entering your project schedule and generating an Earned Value graph, but this is the procedure they use. In the absence of software, you can generate an excel spreadsheet and simply update the numbers every week (or whatever time period works for you), like I said, in 10 minutes or less.

A major assumption of this method is that the task gets completed at a constant rate. If you have a task that requires a major expenditure at some intermediate point you may need to make the necessary adjustments (in #1 above).

How to Analyze the Results

What does it mean? The results of the exercise will give you a number called Schedule Variance, and a graph of the schedule variance over time. The important things to note are:

- Negative schedule variance (i.e. the PV is higher than EV on the graph). The project is behind schedule. The amount tells you something too. If you can compare the negative schedule variance to your estimated cash burn, say the number of people currently working on the project, you can get a quick idea of how bad it is. For example, if you’ve got 3 people working on the project and you’re burning $5,000/week, and a schedule variance of -$4,000, these are bad numbers. You’ve got almost a full week of work to get back on track.

- Increasingly negative schedule variance (i.e. the gap between the PV and EV on the graph is getting bigger) this is an even bigger cause for concern. The project is getting further behind. There is probably some sort of disconnect between the baseline (schedule) developed by the project manager and the work being done on the project. The project completion deadline could be in jeopardy.

How to Use Earned Value to Move Projects Forward

Sometimes knowledge is the only power you need. If you let your project team know what the schedule and cost variances are at regular intervals (a weekly progress meeting, or whatever), I think you’ll be amazed how quickly things get back on track when people get told there is a negative variance. At the engineering company I described above, I don’t have to hold motivational meetings, or yell and scream, or kick up a fuss. Things seem to come into line when project teams are aware that they are behind.

Also, if a negative variance is presented to the project team and a project member doesn’t see it being easily corrected, this information comes out pretty quickly.

It also gives you, the project manager, a fantastic early warning signal of project distress. The numbers will tell you there’s a problem long before you would otherwise notice. And you won’t be able to brush them off so easily either.

Too many technical professionals simply use gut feel for project schedule tracking. If you merely suspect a project of being behind, why not spend the 10 minutes per week and make a quick calculation? Bookmark this page and go through the steps.