Jidoka is the ability of machines and assembly line workers to detect when a quality non-conformance issue has occurred and immediately stop the production line to make the necessary improvements to the process. Jidoka originated in the Toyota Production System, where it was not just the worker’s right to “pull the cord,” but their responsibility.

Far from leaving the inmates in charge of the asylum, jidoka was one of the main reasons why Toyota was renowned for high quality products.

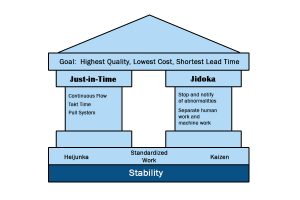

Jidoka was one out of two pillars of the Toyota Production System, the other being just-in-time production.

After Toyota emerged from the second world war in ruins to become the world’s largest automobile manufacturer in the 1990’s, many people tried to determine the secret to their success. Today, the study of this success has developed into the modern methodology of lean manufacturing.

Modern jidoka is done mostly by machines, which perform an inspection or quality measurement prior to releasing the product to the next manufacturing station.

Benefits of Jidoka

Jidoka should be implemented as part of a system, normally that of lean manufacturing. As I describe below, the lean manufacturing methodology is ideally suited to jidoka, and they should not be considered in isolation.

There are three benefits to jidoka:

- Higher Quality

It is difficult to argue that catching defective material prior to assembling a final product will not increase quality substantially. In fact, the quality of Toyota vehicles in the 1990’s was considered without equal, and repair costs were the lowest of any car company. - Worker Respect

Jidoka emphasizes the responsibility and decision making ability of line workers. These workers are given training in problem solving and decision making, and they are trusted to solve the problem quickly and effectively. As a result, workers feel respected and morale is high. - Higher Productivity

Because of the ability of each machine to test the product prior to the next production step, each person can monitor more than one machine.

Jidoka’s origins date back to the early twentieth century, when Sakichi Toyoda (prior to founding the Toyota Motor Company) used a textile loom that, when a thread broke, spun itself out wasting copious amounts of material. He invented a machine that detected the broken thread and automatically stopped the machine, preventing the waste.

Jidoka Autonomation

Toyota coined the term autonomation, which means automation with human intelligence, to represent the machine-based jidoka actions which have largely, but not completely, replaced human jidoka. Although humans can, and do, still “pull the cord,” autonomation represents the machine inspection of parts prior to release to the next production step. Just like the automated textile loom which shut down upon the break of a thread, modern assembly lines should strive to monitor the product and shut down the assembly line if quality metrics are not met.

Jidoka Andon

Andon, japanese for “lamp,” refers to a notification to workers or management that an abnormality is occurring in the production process. This can be a result of:

- Machine downtime

- A quality problem

- Material shortages

- Tooling faults

- Operator delays

An andon board displays notifications of actions required by the production staff. It can also indicate priority, such as green-yellow-red marker. It can also contain production status, for example planned vs. actual production for the period.

The simplest andon is a light that turns on when a problem occurs.

Lean Manufacturing

Today jidoka is a component of lean manufacturing. This methodology seeks to minimize the length of time a product takes to proceed from raw material to finished good. Once a raw material has entered production, it should not stop until the finished product is completed. This is in contrast to traditional manufacturing which seeks to minimize the downtime of machines and people.

Today jidoka is a component of lean manufacturing. This methodology seeks to minimize the length of time a product takes to proceed from raw material to finished good. Once a raw material has entered production, it should not stop until the finished product is completed. This is in contrast to traditional manufacturing which seeks to minimize the downtime of machines and people.

There are five core principles in lean manufacturing:

- Identify Value

The first step is to isolate where the value is. Value is defined as something that someone is willing to pay for, and in most cases that translates into the physical product being produced in the plant. Anything that is not absolutely essential to the value stream necessary to create this product is considered waste. - Map the Value Stream

The item of value is decomposed into its constituent processes. Again, each process must only be absolutely required to create the item of value. Other process based factors such as transportation between processes, warehousing requirements, and delay times are also noted on the value stream map. - Create Flow

Flow refers to the setup of production stations to minimize the duration that each product is waiting for the next step. To accomplish this, all manufacturing steps are designed so that they are the same duration. This duration should be equal to the required plant output to satisfy customer demand, called takt time. If required, multiple, parallel assembly lines are set up, thereby creating a system of small machines rather than one large one. This allows for quick changeover or variations in the final product. - Pull

In lean manufacturing facilities, the production line is pulled by the customer, rather than pushed by the sales department or internal inventory metrics like maximizing equipment efficiency. Once an order is received the assembly line begins production, barring any special circumstances. This is accomplished using a system called kanban. When an order is received, the kanban card is created which moves with the product from raw material through to finished good. The kanban card, which can be a physical card or electronic tracking mechanism, guides production – no kanban card, no production. - Perfection

The lean production system places people at stations where necessary, performing standardized work which is written in well known procedures. This frees up the operators to perform kaizen, or continuous improvement, which refers to the removal of all muda (waste) from the assembly process that does not add to the value stream. That’s where jidoka comes in.

Jidoka is not a strategy meeting or budgeting session. It requires the ruthless, total elimination of all waste. Where waste is identified, the patient is in critical condition and urgent action is necessary to resuscitate it. Anything less is not insufficient for the criticality of the situation.

Jidoka Examples

- In the factory, the pistons are formed in a hot machining process, and prior to being released to the next manufacturing process, they are measured. If the measurement is outside tolerances, a warning light is activated and the assembly line is stopped, alerting the operator to investigate the problem and take the required action.

- In a package sorting plant, a sensor measures the speed of each conveyor belt, and activates a warning light if the speed ever drops below a specified minimum level. This allows the operator to take the required action to ensure the process completes according to the plan.

- In a certain production station in an electronics plant, an operator must physically solder several locations of each circuit together. Once complete, the circuit is attached to a live current to ensure it is flowing. If not, the operator must take the circuit board back and re-work it until it is working.

- A restaurant installs a raw material sensing technology that detects when cheese, bananas, and other raw material bins are below a certain threshold. If so, a light illuminates to alert the restaurant staff that the material is critically low and more must be ordered.

- A vehicle measures its engine temperature and alerts the driver via a dashboard light (an andon) if the engine temperature is approaching an unsafe level, thereby allowing the driver to take action to avoid bigger damages.