When a ship is out on the open sea, the driver, called a Helmsman, is responsible for turning the wheel which in turn moves a rudder back and forth to change directions. When the wind or sea conditions are rough, experienced helmsman use their keen sense of how the ship will react to keep it moving in the right direction. Because the ship doesn’t react right away, the helmsman must anticipate the delay between turning the ship’s wheel and the reaction of the ship.

Managing projects is a bit like steering a ship. The destination is clear, but the actions necessary to get there require careful judgment and experience. When unpredictable weather conditions force the path to change, the project manager must predict the safest, but straightest alternative path, and guide it through the storm.

The destination, that is, the end goal of all projects is to:

- Produce the desired product or service

- Meet the minimum desirable quality level

- Finish on time

- Finish on budget

- Satisfy all stakeholders

There are several project management methodologies out there, but the most popular one is the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), developed by the Project Management Institute. In this article I will provide a quick outline of the methodology of the PMBOK and focus on what a project manager does on a daily basis to manage projects according to this standard.

What is a Project?

Since this is Project Management 101, let’s start at the beginning. A project is defined as “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result.” You might notice the following two words in that definition:

- Temporary. It has a finite start and end date. It does not go on indefinitely.

- Unique. Although some projects look very similar to other projects, the end result is always something new for the world.

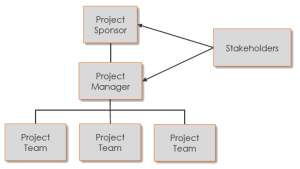

A project has three distinct levels:

A project has three distinct levels:

- Project Sponsor. This person is above the project, usually a superior to the project manager. They often serve as an organizational lead and control project funding.

- Project Manager. The final authority on project work, and person held accountable for the project’s success or failure.

- Project Team. The people who perform the day to day work of the project.

Project Management Process Groups

It’s a complex term for a simple concept, but there are five process groups which are better thought of as phases that almost all projects fit into:

- Initiating. The tasks required to define, create, and fund the project.

- Planning. The project is planned out in sufficient detail to define how the project will produce its anticipated results, manage stakeholder expectations and control the triple constraints of time, cost, and quality.

- Execution. The project work is completed.

- Controlling. This phase involves the tasks required to ensure the project stays on schedule, on budget, and that the requirements are being satisfied.

- Closing. The project is completed in a manner that satisfies all stakeholders.

These phases occur in chronological order except for Controlling, which is performed simultaneously to Execution as the project work advances.

Each phase generates several project management documents. For a small project, this could include:

| Phase | Document |

|---|---|

| Initiating |

|

| Planning |

|

| Execution |

|

| Controlling |

|

| Closing |

|

Each of these documents has a distinct purpose and provides the project manager with a strong foundation to ensure the project’s goals are met.

- Project Charter. This is an optional, organization-level document who’s purpose is to commission the project and authorize the project manager. It contains all of the information that the organization is thinking when initiating the project.

- Project Management Plan. This is the project manager’s guidebook. It is written by the project manager and communicates to all stakeholders how the project will be managed. It sets the expectations and establishes procedures for important items. It is normally written in such a way that it can be distributed to stakeholders but sometimes an internal version must be produced (for example, when there are internal financials disclosed). It includes the schedule and budget, the two things that are often the most important. The project plan is approved by the project sponsor and changes during the project must be made via the Change Log.

- Project Status Reports. These are weekly (or whatever status period works best) reports that are distributed to stakeholders. Their purpose is to keep stakeholders updated as to the status of the project.

- Stakeholder Communications. Often communication is the key factor that allows the project to finish well in spite of the issues that arise. These take the form of standard communications, like investor circulars, newsletters, executive updates, and the like. They can also be informal communications which happen spontaneously during the project.

- Change Logs. Everyone that has managed projects can tell you that they change. The schedule, the budget, the deliverables, the subcontractors, they are all destined to change. Although it is desirable to keep project change to a minimum, a change log is necessary to keep the project plan organized.

- Variance Reports. To keep the project on the straight and narrow, earned value analysis is used to produce variance reports over predefined status periods. These reports can be combined with the regular status reports mentioned above. They provide a quantitative way to measure and report project progress, and an early warning signal when the project is getting behind.

- Project Closure Report. Although this report often ends up in the files, it is important because it ensures the project manager reviews the project success criteria and scrutinizes the final cost, schedule and other factors. This is a project management report, most projects also need technical closure like final documentation, as-built drawings, and administrative items.

Knowledge Areas

The process groups described above are chronological phases in the life cycle of a project. Within each phase, one or more knowledge areas bring the project to life. The phases are vertical and the knowledge areas are horizontal. They might make an appearance in any phase at any time, but they have places where they normally occur.

- Project Integration Management. This knowledge area covers the overall project-based stuff like creation of the project management plan, management of project changes, and so forth.

- Project Scope Management. This includes writing up a scope statement and managing the project scope throughout the project.

- Project Time Management. This knowledge area is generally the most time consuming. It includes dividing the project into tasks, creating the project schedule, and managing changes to it throughout the project.

- Project Cost Management. This knowledge area deals with assigning a cost to each task, rolling it up into an overall project budget, and managing the project budget throughout the project.

- Project Quality Management. This knowledge area involves determining the quality standards that apply to the project and ensuring the deliverables are produced to the standards.

- Project Human Resource Management. This knowledge area covers the project team. Acquiring, developing, and managing the project team are essential to the successful completion of any project.

- Project Communications Management. This knowledge area deals with determining the communication needs of the project stakeholders and making sure they are kept informed throughout the project.

- Project Risk Management. This knowledge area involves identifying the biggest risks to the project’s success and mitigating them by reducing their likelihood or occurrence or size of impact.

- Project Procurement Management. This knowledge area covers the procurement of external contractors, services, and purchase of products and equipment.

- Project Stakeholder Management. Finally, this knowledge area identifies the needs of the various stakeholders and how they will be met.

Professional Project Management

I’ve known many people who were promoted into project management roles, or simply started in one (including me). It is safe to say that at this point in time, professional project management techniques are not a prerequisite for most project management jobs. However, there is clearly a body of knowledge which governs the project management profession, and the more you draw on it, the better you become.

Entire books have been written about this subject, but I will boil it down to the basics here. The above-mentioned project process groups are distinct chronological phases that are occur one at a time. The following six action steps would represent a typical project that proceeds through those phases:

- Draft the Project Charter (if it hasn’t been done) which establishes the purpose for the project and gives authority to the project manager. For small projects or where the lines of authority are obvious, the project charter is optional.

- Create the Project Management Plan. Each knowledge area listed above is covered in the project management plan. The project should be divided into tasks, and each task given a budget as well as start and finish dates. This step should not be taken lightly. It should take long enough to figure out all the pieces and create a coherent “project plan.”

- Obtain Approval. The project management plan should be approved by the project sponsor, and initial communications with stakeholders made as required by the plan. Notice that it is incorrect to make changes to the schedule, budget, or any other part of the project plan without the re-approval project sponsor. For small projects, an approved schedule will suffice.

- Produce Status Updates. The project manager must choose a status period and provide status updates to the project sponsor and stakeholders. I recommend one week because it will work for any size project, but any status period length will do. At the end of the status period, the project manager determines the “percent complete” of each task and performs earned value analysis to determine the project progress. Other knowledge areas come into play as well, such as re-confirming the scope.

- Keep a Change Log. The project plan is not fluid and available to be changed without consultation. When changes must be made, the change log is updated and the project sponsor must re-approve the plan. Any stakeholders that require re-approval must also be informed.

- Produce a Project Closure Report. The project closure report helps you to evaluate the project from the point of view of its initial success criteria and parameters. The lessons learned will be invaluable to your future career as a project manager.

Let me know in the comments how you’ve used these project management practices on your projects.