Above all else a project manager is a leader, therefore developing leadership skills is one of the best ways for a project manager to further their career. To that end, one of the most important traits of a leader is the ability to react swiftly and decisively when unexpected events occur. Project risk management is the division of Project management that helps you do that.

More specifically, a Risk Management Plan is the part of the Project Management Plan that plans, identifies, and analyzes project risks.

Parts of a Risk Management Plan

- Risk Planning

- Risk Identification

- Risk Analysis

- Risk Response Plans

- Risk Register

Risk Planning

Project risk is defined by the Project Management Institute as an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on one or more project objectives. Risk management is the process of identifying, analyzing, mitigating, and communicating risks.

When a risk event occurs, it is no longer uncertain. It becomes an issue.

Risk can be broken down into two underlying components:

- Probability: The likelihood of the event happening.

- Impact: The consequences of the risk event.

The formula for risk is very simple:

To illustrate, a plane crashing into your office has a high impact, but a low probability. In fact the probability is so low that the overall risk is probably insignificant. On the opposite end of the scale, a road construction project getting delayed due to rain is an event with a low impact but a high probability of occurrence. Thus, it is a significant risk.

A Risk Management Plan should begin with an analysis of the risk tolerance of the organization.

- What projects have been completed in the past and what unexpected issues occurred?

- What was the response of the organization?

- What permanent changes were made? Were they justified?

- Did the response cause a corresponding loss of business?

- Did the response cause a corresponding loss of future projects?

Another part of the risk planning portion of the Risk Management Plan is the definition of risk levels. Here is an example:

- Very Low: The event is highly unlikely to occur under regular circumstances.

- Low: The event is unlikely but should be noted by the project team.

- Medium: The event has a normal chance of occurring and the project team should be aware of it.

- High: The event has a reasonable chance of occurring. It should be regularly discussed and mitigation actions taken.

- Very High: The occurrence of the event should be actively managed and mitigation actions taken.

A good brainstorming tool is to consider the assumptions made by the project. Most projects have disclaimers in their underlying contracts absolving the performing party of various obvious risks, but what about the next most obvious ones?

- What assumptions has the project budget made?

- What assumptions has the project schedule made (completion date, milestones, etc.)?

- What expertise or prior experience does the company have in this work? How long ago was this experience? What areas require additional training?

- Which relationships are being assumed to be strong that are not necessarily (owner, sponsor, client, contractor, consultant)?

- How many previous projects with similar components have been completed successfully? What were the project issues?

Risk Identification

To begin the risk analysis process, risks must be identified. The logical process of risk identification involves the following steps:

- Consider the critical success factors (CSF) of the project. Since a risk is something that affects project success, you need to be clear on what project success means. If you haven’t developed CSF’s, you need to do that first.

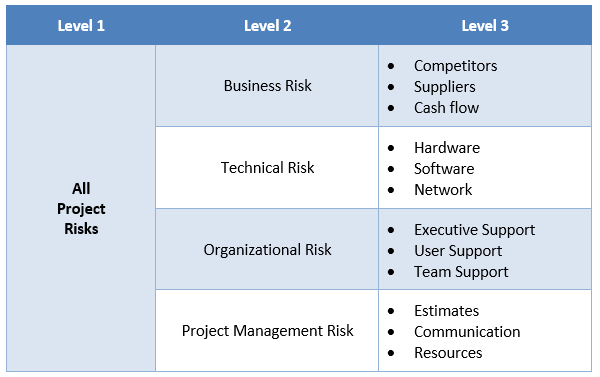

- Develop a Risk Breakdown Structure. This is a table that establishes the major categories of the project’s risk. It’s an easy step to skip, but you will miss risks because it’s natural to focus on just one category. For example, for a software project you might focus only on the hardware, network, and so forth but miss cost estimates or communication risks.

- Use each of the methods of risk identification below to categorically develop the project’s risk register.

The methods of determining risks are as follows:

- Checklists

If you don’t already have one, try to develop a checklist for risks that is specific to your organization. This will allow you to quickly realize which ones are the most important and in which circumstances they apply. We have a checklist which can be a good starting point, but it is better to have a more specific one. - Lessons learned

Only once have I encountered an organization that maintains a lessons learned database, but it is an amazing tool for them. It’s a highly visible record of problems encountered, mistakes made, and what the project manager would do differently in future projects. When you’re starting a new project and you spend a few minutes reading that, how can you go wrong? - Subject matter experts

There is essentially no substitute to having experts who know the subject matter advising you of the risks involved with the work. Often they are in other departments but their advice is second-to-none. - Documentation review

This involves learning about the project, its technical details, and its people. Pay close attention to the unusual parts, the ones that aren’t everyday, simple tasks. - SWOT Analysis

A Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats analysis will assist in drawing out the risks inherent in the project. Particularly the Weaknesses and Threats quadrants can yield some new risks you didn’t think of before. - Brainstorming

Whether alone or in a group, brainstorming involves focusing on quantity over quality. Just write everything you can think of on paper, and then come back and narrow down the list later. - Delphi technique

This method involves querying a group of people or subject matter experts, then sharing all of the answers anonymously with the whole group and letting them revise their original answers. After several rounds a consensus should emerge. - Assumptions analysis

Every project contains certain underlying assumptions upon which its business case is built. Identifying these assumptions, and analyzing their reliability, can result in the identification of new risks. - Influence Diagrams

Drawing out a simple decision network for the major turning points within a project can yield the important risks.

Of course, you will never be able to determine all of the risks to the project. The real world contains way too many variables. But a strong risk identification process gives the project manager the confidence to take decisive action on any issue that arises. And this is actually the bigger benefit to project risk management. Although many project managers skip or undervalue the risk management step, strong leaders are truly made here.

Once the risks have been identified, it’s time to prioritize them via risk analysis.

Risk Analysis

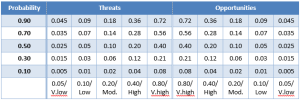

Since risk is defined as Probability x Impact, both factors need to be considered when determining the priority of each risk event. Thus, the probability-impact matrix gives you a more detailed definition of the probability and impact structure used by the risk register (more on that later). The matrix helps you to consider both factors and sets the stage for the determination of numerical probability and impact values for each risk event.

Each risk in the register is given a probability rating and an impact rating. These are then multiplied together to get the priority, and the list is then sorted by priority. The risk management team then drops the risks they deem insignificant to come up with a final risk list.

The probability and impact ratings can be on any scale. Although a 1-10 scale is easy for small projects, a 1-100 scale is often intuitive for the probability because it is effectively a percentage, and a monetary (dollar) value is often intuitive for the impact rating. Thus you are effectively saying, for example, that a certain risk has “a 25% probability of costing $4,000 extra.”

The risk priority is then the multiplication of the two, or 25% x $4,000 = $1,000. Theoretically, this is the ideal contingency for that risk. You could add that amount to the project budget to account for that risk, and all of the other contingencies for all of the risks, combined will just cover the the possibility of any one of them happening.

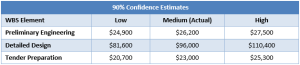

In addition, a good risk management plan should have some sort of confidence range estimates attached to budget numbers, particularly for larger, more complex projects. These are simply an analysis by the risk management team (or project manager) of the potential deviation from the project plan. They are excellent for management discussion.

It can be as simple as low/medium/high probabilities or as complex as statistical analysis of the probability of meeting deadline dates.

Risk Response Plans

At this point the risk register contains all of the most important risks, ordered by priority. But what happens when the risk occurs? Unless the risk register helps the project manager make fast, effective decisions it was all a great paper pushing exercise. That’s why you can’t forget the development of risk response plans.

There are four possible ways to respond to a risk event.

- Avoid. Eliminate the threat or protect the project from its impact. Here is a list of common actions that can eliminate risks.

- Change the scope of the project.

- Extend the schedule to eliminate a risk to timely project completion.

- Change project deliverables.

- Clarify requirements to eliminate ambiguities and misunderstandings.

- Gain expertise to remove technical risks.

- Transfer. Offload the impact of the risk to a third party.

- Direct methods: Insurance, warranties, or performance bonds.

- Indirect methods: Unit price contracts instead of lump sum (or vice versa depending on which side of the contract you’re on)

- Legal opinions

- Mitigation. Reduce the probability or impact of the risk. This is not always possible and often comes with a price that must be balanced against the value of performing the mitigating action. Brainstorm different actions that would reduce the project’s risks and take the actions up front if you have to.

- Accept. All projects contain risk. As a minimum, there is the risk that the project doesn’t accomplish its objective. It follows that project stakeholders must accept certain risks. Tolerating risk is a strategy like any other, and should be documented and communicated like any other strategy. Risk acceptance can be passive, whereby the consequences are dealt with after the risk occurs, or active, whereby contingencies (time, budget, etc.) are built in to allow for the consequences of the risk to the project.

The four risk response strategies can be applied to overall project risk as well.

Risk Register

Putting it all together, the risk register contains the prioritized ranking of the most important risks for the project. The risk register is usually in table form and has the following columns:

- Risk Name/Description

The risk event can be described with descriptors, such as “The contractor could incur additional material supply cost and attempt to pass this on to us.” Risk identification is a fairly time consuming endeavor that should not be skirted. See our potential risk checklist. - Probability

The likelihood of the event occurring. If possible, a numeric value between 0 and 1 should be used which can be multiplied by the Impact (next column) to determine meaningful risk values. But for smaller projects a 1-10 scale or “low/medium/high” is also satisfactory. - Impact

The impact of the risk event. Again, a number between 0 and 1 or a dollar value is good because it results in meaningful overall risk values. - Risk

Since Risk = Probability x Impact, multiply the two previous columns together. If a qualitative scale like low/medium/high was used, simply use the same qualitative scale to describe the overall risk level in light of the probability and impact of the event. - Priority

A good risk management plan will identify the most important risks to the project. In this column, the risks will be prioritized starting from 1 and moving consecutively down until they are all prioritized. Project sponsors, clients, and owners love this, by the way. - Response Plans

To complete the risk register, a response plan should be created for the top 3 (approximately) risks to the project. Alternatively, they could be included outside of the table, but often a quick synopsis can make the risk register stronger. Something like: “Account for project team, call hazardous spill group, and fill out incident form.” Memorize the top 3 risk responses.

The summer olympics have to plan for everything from a riot to a terrorist attack. A risk response team develops literally thousands of risk response plans. A part of the $15 billion budget is devoted to ensuring that thousands of workers are briefed on the correct response procedures for hundreds of different risks. And when unexpected issues arise, there’s a good chance somebody has already considered the response and that a risk response fund is already available for it.

Therefore, if the world’s largest project (maybe) puts that much emphasis on risk management, isn’t it likely to be worth the corresponding percentage of time and budget for small projects? True leadership demands nothing less.

Good luck with your Risk Management Plan, and let me know if you have any other tips and techniques.