A cost benefit analysis is a project selection method in which a common metric is used to compare a project’s costs and the benefits it provides. It is used in public projects (like road building) or projects where the end product is not purely monetary.

The cost benefit analysis is performed by computing the net present value of the project with the net present value of the project’s benefits.

Intangible Benefits

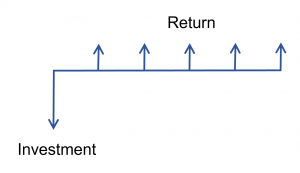

In a traditional investment analysis, an investment is made with an expectation of a return, like this:

What happens when the return is of an intangible form or doesn’t generate a revenue stream (partial or complete)?

In this case, the return must be quantified in other terms to compare it with the money used to pay for it, in order to get an apples to apples comparison and justify the feasibility of the project. That’s where cost-benefit analysis comes in.

For example, projects like building a road, enhancing/restoring the environment, developing a safety program, or performing research do not generate a revenue stream, hence they cannot be analyzed via investment return metrics.

Projects with intangible returns tend to be concentrated within government, hence governments tend to have strong policies and procedures for performing cost benefit analyses. For that reason, if your project is by or for a government the first place to look is a manual or procedure guide for that jurisdication.

The Willing To Pay (WTP) Principle

Cost Benefit Analysis is built upon the idea that even though a benefit is not monetary, someone is willing to pay for it. This is the foundational justification for the expenditure. It is the overarching theme of the cost benefit report (if one is produced) and focuses the analysis on the monetary value of the benefit.

It is called the Willing to Pay (WTP) Principle.

Obviously, the people who are experiencing the benefits are not paying for them (at least full price) or traditional capital budgeting methods would be more appropriate. The Willing to Pay Principle asks, if the end users had to pay, how much would they be willing to pay?

Hence, the cost benefit analysis focuses on defining the intangible benefit in monetary terms.

There are very often market based value indicators which provide a rough guide for the value of an intangible benefit. For example,

- What similar products or services are being paid for in a free market. What price are they being sold for?

- What are the costs (direct and indirect) for the stakeholder to experience the benefit?

- What are the underlying features of the benefit that have an established market value?

- If the product is part of a larger network, what is the market value of the network that can be subdivided into its smaller parts.

Conversely, the size of the investment can be analyzed. When others have spent money on the same benefits, a rough guide for value has been created, for example:

- What are the viable upper and lower bounds of the investment? That is, how big of an investment is too high? Too low?

- What other similar projects have been completed, and how much was their investment? What was the level of stakeholder acceptance?

Cost Benefit Analysis and Risk

The production of a cost benefit analysis requires a strong knowledge of project risk. The intangible benefits being analyzed are prone to being under or overestimated. The benefits might not materialize, or the risk of the benefit not being enjoyed are too high.

The production of a cost benefit analysis requires a strong knowledge of project risk. The intangible benefits being analyzed are prone to being under or overestimated. The benefits might not materialize, or the risk of the benefit not being enjoyed are too high.

For example, a new environmental enhancement project might be a success in its construction, but there is a risk that the public does not spend their time to enjoy it.

Risk has two underlying factors:

- Probability

The risk level of an event is proportional the odds of it occurring. - Severity

The risk level of an event is proportional to the size of the impact it makes.

For example, your office might be hit by an airplane (a “risk event”). The probability is very low, but the severity is very high. One variable is positive and the other negative, and they actually cancel each other out. However, for most people the low probability outweighs the high severity, allowing you to conclude that this risk event is not worth the creation of a risk response plan.

How to Perform a Cost Benefit Analysis

There are four steps to carrying out a cost benefit analysis:

- Identify Stakeholders and Benefits

- Develop Alternatives

- Assess Costs and Benefits

Step 1: Identify Stakeholders and Benefits

The first step is to identify the people or groups who are receiving the benefits, called stakeholders. Usually there is one major stakeholder, however it should not be underestimated that there are usually minor stakeholders which fly under the radar, and enough effort should be made to identify all of them.

Secondly, the benefits to that stakeholder group should be defined. At this stage, the monetary aspect is not important, rather the exact definition of the benefit – who, what, when, where, why, and how.

Step 2: Develop Alternatives

Cost benefit analysis is used to compare projects to each other, but also to compare alternatives within projects. For example, the type of environmental solution, or the size of the safety program, or the width and length of the road. All the alternatives must be considered in tandem with the benefits of each option. The stakeholders usually expect an analysis of the alternatives.

Step 3: Estimate the Cost

There are two sides to the financial coin of a cost-benefit analysis: The Cost (investment) and benefits. In this step, we address the costs. In the next step, we will tackle the benefits.

Costs are usually estimated using traditional project estimating techniques such as bottom up estimating in conjunction with analogous and parametric estimating. This works by dividing the project into tasks. Each task is estimated using either:

- Analogous: The task is estimated from the actual cost from a previous project, for example,

The concrete for our previous project cost X, therefore the concrete for this project should cost Y.

- Parametric: The task is estimated using a unit rate, for example,

The local Construction Association estimates that concrete costs X per square foot.

The estimates for each task are then conglomerated into an overall project estimate using bottom up estimating. Conversely, the analogous and parametric technique can be applied in a top down fashion, like this:

- Analogous: The City down the road built their runway for a cost of X, therefore ours should cost Y.

- Parametric: The federal government database lists a runway cost of X per square foot.

Step 4: Determine the Benefits

The benefits are generally the part that requires the most work because they are difficult to define. And the general pattern in life holds, that the most difficult part is the one that makes or breaks the analysis. Since the cost benefit analysis is only as strong as the benefits definition, I will start by outlining the 3 most common situations and then branch into general valuation methods for intangible assets.

- Value of human life (safety)

This topic is always controversial, but fortunately in most jurisdictions a workers compensation board (WCB) is tasked with wrestling with this question so that individual market participants don’t have to. Compensation rates for loss of life or limb are set by the WCB and all corporations pay premiums (like an insurance policy) which are increased or reduced based on its safety record and externally audited safety programs or initiatives.A company is considering spending $100,000 to produce a safety program which will reduce its WCB premiums by $10,000 per year. The WCB has determined the value of the benefit. - Value of environmental degradation / enhancement

People want a healthy and thriving environment, and are willing to pay for it. Environmental enhancement projects come with a benefit that can be defined based on the public’s willingness to pay for all projects of that type. A government sets a budget for certain types of environmental projects, and this budget defines the public’s willingness to pay (WTP), that is, the demand for that type of project. Projects “compete” for a piece of that pie, thereby defining their value.A cost benefit analysis is being developed for a wetland restoration project. The cost of the project is estimated at $1 million. To determine the benefit, the project team consults the government budget of $10 million for all wetland restoration projects for that year. Each of the project managers for the projects under consideration are consulted to determine that the budget represents $10,000 per acre of restored wetland. This is the value of restoring wetland. Since the project is to restore 200 acres, the benefit is $2 million, double the project budget. Hence, the project should be approved.Environmental remediation projects, on the other hand, can usually be valued more directly, whereby a new development can proceed because the previous environment has been cleaned up. The value of the remediation is the value of the new development that can occur.

A developer wants to build a large condo on a hill with a pristine view. The value of the view is determined based on how many people view it, and how much they would pay to use it. - Value of social impact

People want to have relationships and interact with each other. Projects that influence social structures, whether positive or negative, have a benefit that must be defined. Disruption of people’s lives usually carries a monetary value which is easy to define, such as the construction of a new house or additional travel to a job. These must be meticulously estimated, but it’s the non-monetary disruption which requires the most analysis. The key to valuing these social impacts is to find the precedents. Generally, established precedents are available even if they are in another location or slightly different, and research needs to be conducted to determine the precedent for this type of disruption.A city government wishes to build a new runway at the local airport. It requires the demolition of some residences in the path of the new runway. The benefit is a negative social benefit. The government officials consult the average compensation for expropriation for other projects within that city as the starting point for negotiations.

The benefits are quantified to allow decision makers to take the best course of action.

Methods of Valuing Intangible Assets

Although the specific methods of dealing with the three main situations are defined above, we present the following as a checklist to define the value of any intangible asset.

- Hedonic value

This refers to valuation of an asset through known values of characteristics or attributes of that asset. For example, the value of a park is based on the size of the park and the number of visitors. - Travel cost method

This method values an intangible asset based on the cost stakeholders pay to experience it. Its name refers to the travel cost to visit an environmental attraction, but can include any cost to experience the intangible asset. - Averting behavior method

This method seeks to determine what behaviors are being modified due to the intangible asset. For example, the people of a community no longer drive to a more distant park after a park is built in their community, saving them on the cost of fuel. Hence, this cost puts a floor under the asset’s value. - Cost of illness method

This method seeks to quantify the medical costs associated with an intangible asset. For example, the new park decreases the incidents of heart attack because the local people are more active. The cost of treating a heart attack can then be defined from local medical data. - Stated preference method

This method seeks to value an intangible asset by directly asking stakeholders how much they would be willing to pay for something. This is accomplished using surveys, interviews, and questionnaires. These results can be skewed based on participants not having the full amount of data available. - Benefit transfer method

This method uses a previous cost benefit analysis to determine the benefits for a new cost benefit analysis. Of course, this does not introduce any new information, but it is widely used in the health and environment fields.