Managing projects is like steering a ship. When the wind or sea conditions are rough, experienced helmsman use their keen sense of how the ship will react to keep it moving in the right direction. Because the ship doesn’t react right away, the helmsman must anticipate the delay between turning the ship’s wheel and the reaction of the ship.

The destination is clear, but the actions necessary to get there require careful judgment and experience. When unpredictable weather conditions force the path to change, the project manager must predict the safest, but straightest alternative path, and guide it through the storm.

Project Success

The definition of project success is specific to each project, but there are common items that apply to most. As a minimum, the goal of all projects is to produce the desired product or service. In addition, most projects count one or more of the following as success criteria:

- Finish on time

- Finish on budget

- Meet the minimum desirable quality level

- Satisfy all stakeholders

In order to achieve the project’s success criteria, project management methodologies have been developed that standardize project management practices and tasks.

Project Management Methodologies

Among other proprietary methodologies, there are three methodologies for project management in the world today:

- Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) developed and maintained by the Project Management Institute (PMI) based in the United States.

- PRINCE2, which is developed and maintained by Axelos in the UK.

- The IPMA Competence Baseline, developed by the International Project Management Association (IPMA).

The popularity of each methodology varies from country to country. Worldwide, the PMBOK is the most widely followed, while PRINCE2 is more popular in the UK and several of its commonwealth countries. The IPMA Competence Baseline has a smaller following than the first two. It is designed as a standard on which to judge the competence of project managers, to serve as a guideline for the IPMA certification although it does contain a full project management methodology.

All three methodologies come with project manager certification programs. The Project Management Professional (PMP) offered by the PMI is likely the most popular, although the PRINCE2 Practitioner claims to have more certifications. However, because it does not expire and has no ongoing professional development requirements, many people question how many of those certifications are active (non-practicing, retired, leisurely holders, etc.).

Because the PMBOK is the most popular methodology throughout the world, I will use it in this article to outline what the process of project management looks like.

What is a Project?

Let’s start at the beginning. A project is defined as:

A temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result.

You might notice the following two words in that definition:

- Temporary. It has a finite start and end date. It does not go on indefinitely.

- Unique. Although some projects look very similar to other projects, the end result is always something new.

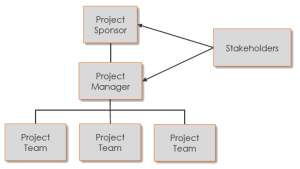

A project has three distinct levels:

A project has three distinct levels:

- Project Sponsor. This person is above the project, usually a superior to the project manager. They often serve as an organizational lead and control project funding. They accept the project’s deliverables.

- Project Manager. The final authority on project work, and person held accountable for the project’s success or failure.

- Project Team. The people who perform the day to day work of the project.

Project Management Process Groups

It’s a complex term for a simple concept, but there are five process groups which are better thought of as phases that almost all projects fit into:

- Initiating. The tasks required to define, create, and fund the project.

- Planning. The project is planned out in sufficient detail to define how it will produce its anticipated results, manage stakeholder expectations and control the triple constraints of time, cost, and quality.

- Execution. The project work is completed.

- Controlling. This phase involves the tasks required to ensure the project stays on schedule, on budget, and that the requirements are being satisfied.

- Closing. The project is completed in a manner that satisfies all stakeholders.

These phases occur in chronological order except for Controlling, which is performed simultaneously to Execution as the project work advances.

To keep the ship going in the right direction, each phase generates several project management documents. For a small project, this includes:

| Phase | Document |

|---|---|

| Initiating |

|

| Planning |

|

| Execution |

|

| Controlling |

|

| Closing |

|

Each of these documents has a distinct purpose and provides the project manager with a strong foundation to ensure the project’s goals are met.

- Project Charter. This is an optional, organization-level document who’s purpose is to commission the project and authorize the project manager. Although items like project scope and deliverables might not be fully established yet, the project charter documents “what the organization is thinking” when initiating the project.

- Project Management Plan. This is the project manager’s guidebook. It is written by the project manager and communicates to all stakeholders how the project will be managed. It sets the expectations and establishes procedures for important items. It is normally written in such a way that it can be distributed to stakeholders but sometimes an internal version must be produced (for example, when there are financial metrics disclosed). It includes the schedule and budget, the two things that are often the most important factors to project success. The project management plan is approved by the project sponsor and changes during the project must be made via the Change Log.

- Project Status Reports. These are weekly (or whatever status period works best) reports that are distributed to stakeholders. Their purpose is to keep allstakeholders updated as to the status of the project.

- Stakeholder Communications. Strong communication can bridge the divide between stakeholders when project issues arise. In addition to informal, spontaneous communication as required, most projects have standard communication requirements like progress updates, investor circulars, newsletters, and the like. These should be documented and tracked.

- Change Logs. Everyone that has managed projects can tell you that the final outcome is rarely the exact same as it was originally envisioned. The schedule, the budget, the deliverables, the subcontractors, they are all destined to change. Although it is desirable to keep project change to a minimum, a change log is necessary to keep the project plan organized.

- Variance Reports. To keep the project on the straight and narrow, earned value analysis is used to produce variance reports over predefined status periods. These reports can be combined with the regular status reports mentioned above. They provide a quantitative way to measure and report project progress, and an early warning signal when the project is getting behind.

- Project Closure Report. Although this report often ends up in the files, it is important because it ensures the project manager reviews the project success criteria and scrutinizes the final cost, schedule and other factors. This is a project management report. Most projects also need technical closure like final documentation, as-built drawings, and administrative items.

Professional Project Management

What, then does professional project management look like on a day to day basis?

I’ve known many people who were promoted into project management roles, or simply started in one (including me). It is safe to say that at this point in time, professional project management techniques are not a prerequisite for most project management jobs. However, the Project Management Body of Knowledge governs the project management profession, and the more you draw on it, the better you become.

Entire books have been written about this subject, but I will boil it down to the basics here. The above-mentioned project process groups are distinct chronological phases that occur one at a time. The following six action steps would represent a typical project that proceeds through those phases:

- Draft the Project Charter If it hasn’t been done outside (above) the project, creating a project charter will establish the purpose for the project and give authority to the project manager. For small projects or where the lines of authority are obvious, the project charter is optional.

- Create the Project Management Plan. Every knowledge area is covered in the project management plan. The project should be divided into tasks, and each task given a budget as well as start and finish dates. This step should not be taken lightly. It should take long enough to figure out all the pieces and create a coherent “project plan.”

- Obtain Approval. The project management plan should be approved by the project sponsor, and initial communications with stakeholders made as required by the plan. Notice that it is incorrect to make changes to the schedule, budget, or any other part of the project plan without the re-approval of the project sponsor. For small projects, an approved schedule will suffice.

- Produce Status Updates. The project manager must choose a status period and provide status updates to the project sponsor and stakeholders. I recommend one week because it will work for any size project, but any appropriate status period length will do. At the end of the status period, the project manager determines the “percent complete” of each task and performs earned value analysis to determine the project progress with respect to the schedule and budget. Other knowledge areas come into play as well, such as re-confirming the scope.

- Keep a Change Log. The project plan is not fluid and available to be changed without consultation. When changes must be made, the change log is updated and the project sponsor must re-approve the plan. Any stakeholders that require re-approval must also be informed.

- Produce a Project Closure Report. The project closure report helps you to evaluate the project from the point of view of its initial success criteria and parameters. The lessons learned will be invaluable to your future career as a project manager.

Project Control

If there’s one fundamental skill for the project manager, it’s ensuring that projects finish on time and budget. Fortunately, the Project Management Body of Knowledge has plenty of guidance on this. It’s called Earned Value Management, and it works amazingly well.

This is how it works. At regular status intervals, the project manager (or their designate) does the following things:

- Determine the Planned Value (PV) for each task. This is easier than it sounds. It requires taking the number of days planned to be complete at the status point and multiplying by the task budget. For example, if the task “cut fenceposts” has a schedule of Jan. 1 – Jan. 10, and it’s Jan. 3 at the status point, the planned value is 30% of the task budget.

- Determine the Actual Cost (AC) of each task. Most organizations track this very well. If you need to add up receipts or collect expenditures manually (or account for labor, etc.), you will need to arrive at an actual cost for each task at the status point.

- Determine the Earned Value (EV). Each task is assigned a percent complete and this is multiplied by the task’s budget. For example, if the “cut fenceposts” tasks is 50% complete, the EV is simply 50% of the task budget.

- Calculate Schedule Variance (SV). This metric tells you how far ahead or behind schedule the project is. The formula is simple:

- SV = EV – PV

- Calculate Cost Variance (CV). This metric tells you how far over or under budget the project is. The formula is also simple:

- CV = EV – PV

The Schedule Variance and Cost Variance are placed into a status report and distributed to management and stakeholders. They are also fantastic early warning signals to the project manager that a project has veered off course. They give you the signal early when it is very easy to correct.

There are other earned value metrics which report the project status in various ways, for example on a percentage basis, amount of budget required to finish the project, and expected budget at completion, in fact entire books have been written about earned value analysis. We cannot outline every metric and tracking procedure in this article but we encourage you to visit our earned value tutorial if you are interested further. Suffice it to say, it is possible to use project management theory to keep your projects on time and budget.

I hope this helps you chart the right course and keep your ship steady during the inevitable storms that every project must navigate through. Let me know in the comments what your experience is and how you’ve made a difference with project management fundamentals.