A business case is the justification an organization uses for making a decision or undertaking an initiative.

Its format can range anywhere from a formal report to an informal presentation or memo.

Business cases are the foundation upon which all business is built. New capital projects, process improvement initiatives, growth strategies, and the like are all dependent on a strong financial and/or cost-benefit justification, which is found in the business case.

Since business conditions change, the business case can also change throughout the project that it justifies. In this case, the project must be re-evaluated.

Furthermore, inadequate business cases undermine projects. They lead to a poor understanding of the underlying economics and contribute to poor project scope definition, which leads to scope creep, as well as the inevitable mid-project budget and schedule changes.

To put the house on a solid footing, a business case consists of 4 parts:

- Problem/Opportunity

- Evaluation of Alternatives

- Recommendation

- Evaluation

Problem/Opportunity

A description of the problem or opportunity under consideration starts the process. This introductory section contains the following information:

- Stakeholder analysis

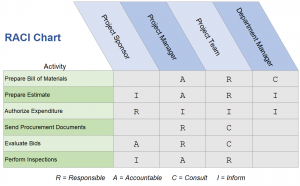

Stakeholders are anyone who has an interest in, or power over, the project, whether their impact is real or perceived. This includes the executive and project sponsor (above), other organizations and external stakeholders (sideways), and the project team (below). The stakeholders and their levels of influence can be communicated with a RACI chart (pronounced “racy”) whereby each stakeholder is classified into the categories of Responsible, Accountable, Consult, or Inform.

- Current Situation Statement

A statement of the current situation together with an analysis of how it impacts the organization, its pros and cons, and its effects on stakeholders serves to provide context. Lots of data is usually essential here, for example money lost per transaction, website visitors, market share, or upward and downward trends. - Organizational Goals and Objectives

The organizational strategy, values, and mission statements, if available, serve to ground the business case in the foundation of the company, providing needed buy-in. Goals should be SMART:- Specific. Clear, concise, and observable.

- Measureable. The outcome must be quantifiable and able to be tested.

- Achievable (aka Attainable or Assignable). The goal must be realistic and the resources must be available to achieve it.

- Relevant. It should be aligned with the organization’s mission and vision.

- Time-bound. It should be accomplished in a defined time period.

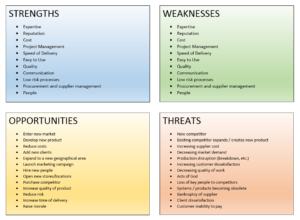

- SWOT Analysis

A Strengths-Weakness-Opportunities-Threats matrix is a depiction of a CEO’s daily thought process that provides an invaluable insight into the business context of the project. The four elements are placed into four boxes. The top two boxes (strengths vs. weaknesses) are pitted against the bottom two (opportunities vs. threats) to evaluate the intangible market-based factors that weigh into the feasibility decisions of the project.

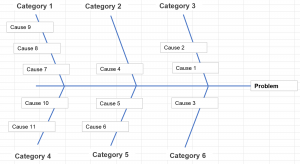

- Root Cause Analysis

Every business problem has one or two (at most) root causes without which the problem would not have happened, and sometimes many other causal factors that exaggerated the problem but are often confused with the root causes. Root cause analysis utilizes the 5 Why’s, in which the proponent asks the question “why did that happen” five times to get the root cause. Fishbone diagrams are popular in business case documents, which display the various sequences of events that lead to the problem.

- Analysis of Existing Capabilities

The organization may possess the in-house resources to solve all or some of the problem already. These resources are analyzed to determine their availability, skills or knowledge, and capability.

Evaluation of Alternatives

Once the problem or opportunity is defined, the available options to address it are determined. This can include:

Once the problem or opportunity is defined, the available options to address it are determined. This can include:

- Delaying the solution is quite often valid, since expenditures must be balanced with competing priorities.

- Performing a partial solution can be a valid option, to perform only the highest priority items.

- Comparing several levels or stages of solution to determine the best one.

Potential solutions are obtained using several methods:

- Brainstorming

Anything and everything is thrown onto a whiteboard (or tracking medium) and then whittled down to the most important ones. - Document analysis

The related organizational documentation, historical correspondence, review of government files, and so forth, can yield insights that were not available otherwise. - Facilitated workshops

Stakeholders are brought together to discuss their requirements and agree on a solution. - Interviews

Stakeholders are consulted in a one-to-one format to gain their insight into project requirements. - Observation

The business processes are observed and insights gleened from watching people do their jobs.

The tools of cost-benefit analysis are employed to compare the options and choose the right one to proceed with:

- Net Present Value (NPV) is the value, in today’s currency, of the full series of cash flows (inflows and outflows) represented by an investment.

- Payback Period (PBP) is the length of time required to recover an initial investment. It is popular in the relatively common situation where a single, large expenditure is followed by an ongoing income stream.

- Return on Investment (ROI) is the percentage return on an initial project investment.

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the growth rate of the project investment, incorporating both the initial and ongoing costs.

- Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is used for investments with non-tangible returns, like roads and bridges.

Generally, all of the methods are calculated and the decision is made qualitatively with the knowledge of the pros and cons of each method.

Recommendation

The alternatives are prioritized and the highest priority option is chosen. The constraints, assumptions, and risks for each option are determined and summarized. The decision can be made (and justified) in several ways:

- MoSCoW identifies the features of each alternative, such as price, quality, production time, etc. and classifies them into the groups of:

- Must haves

- Should haves

- Could haves

- Won’t haves

- Multivoting makes a decision democratically via a structured vote among stakeholders.

- Time-boxing establishes a fixed time limit and forces prioritization of the alternatives according to what can be accomplished in that time period. Alternatively, a budget could also be the time-box factor instead of schedule.

- Weighted ranking lets stakeholders provide a 1, 2, 3,… rank to each alternative and adds them up to determine the highest (or lowest) score. The ranks could be weighted, for example, a 50% weighting is applied to a number 1 rank, and 25% weightings to both number 2 and 3.

A strong recommendation achieves buy-in. It is justified in facts and analysis, and provides a safe place to fall back to when things change – It puts the project on solid ground. You don’t have to know exactly what business conditions will be like in the future, but if the best facts and analysis are used to justify a conclusion, the decision makers can feel comfortable they did the right thing knowing what they did at the time.

Evaluation

Finally, there no point in pursuing a business opportunity if the results will not be measured to determine their success or failure. For that reason, the business case contains the metrics by which the project results will be measured. Project success criteria are established on a high level and measurement methods established. The project deliverables are determined and existing baselines are measured to provide an adequate comparison with the existing situation.

Stakeholders buy-in is obtained to ensure that the maximum likelihood of project success.

For example, a new software product must reduce bookkeeping time by 25%. The existing bookkeeping time is measured to determine that it is 40 hours per week, and the project will be considered a success if this is reduced to 30 hours per week.

Conclusion

A business case is a valuable project document that provides the project management team insight into the justification for the project and the business goals that the project is targeting. It is a living document that is adjusted based on changes to the business needs and environment (internal or external). A strong business case puts the project on a solid foundation and provides an anchor for project success.